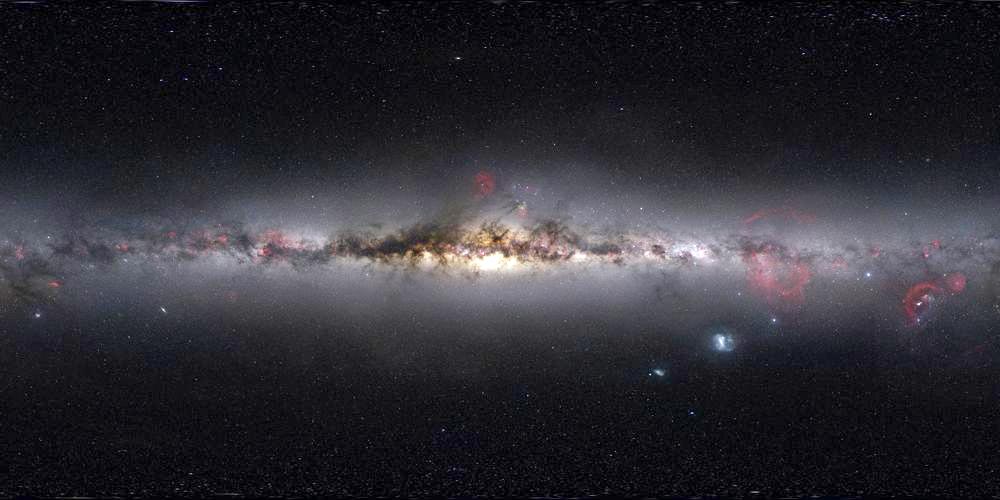

This stunning 360 degree panorama of the night sky was stitched together from 37,000 images by a first-time astrophotographer.

Nick Risinger, a 28-year-old native of Seattle, trekked more than 60,000 miles around the western United States and South Africa to create the largest-ever true-color image of the stellar sphere. The final result is an interactive, zoomable sky map showing the full Milky Way and the stars, planets, galaxies and nebulae around it.

“The genesis of this was to educate and enlighten people about the natural beauty that is hidden, but surrounds us,” Risinger said.

The project began in March 2010, when Risinger and his brother took a suite of six professional-grade astronomical cameras to the desert in Nevada. By June, Risinger had quit his job as a marketing director for a counter top company to seek the darkest skies he could find.

MicroLine ML8300 Array Used for the project

Every night, Risinger and his father set up the cameras on a tripod that rotates with Earth. The cameras automatically took between 20 and 70 exposures each night in three different-color wavelengths.

Risinger sought out dry, dark places far from light-polluting civilization. Most of the northern half of the sky was shot from deserts in Arizona, Texas and northern California, although Risinger had one clear, frigid night in Colorado.

Nick Risinger and his MicroLine ML8300s in Colorado

“It was January and we were hanging out in Telluride waiting for the weather to clear in Arizona or Texas,” he said. “Finally we realized the weather was hopeless down south, but it was perfectly clear where we were.” They drove an hour away, set up near a frozen lake, and sat in their car with the heat off for 12 hours as the temperature outside dropped to minus 6 degrees Fahrenheit.

“I would have loved to turn the car on for heat, but I was afraid the exhaust would condense on the equipment and make a shutter freeze or ice up the lenses,” Risinger said. “Certainly it was the coldest I’ve ever been, but I’ve still got all 10 toes and fingers.”

Risinger plans to sell poster-sized prints of the image from his website and is looking for someone to buy his cameras, but otherwise has no plans to make money from his efforts. He wants to make the panorama available to museums and planetariums, or modify it for a classroom tool.

“When Hubble shoots something, it’s a very small piece of the larger puzzle. The purpose of this project is to show the big puzzle,” he said. “It’s the forest-for-the-trees kind of concept. Astronomers spend a lot of their time looking at small bugs on the bark. This is more appreciating the forest.”